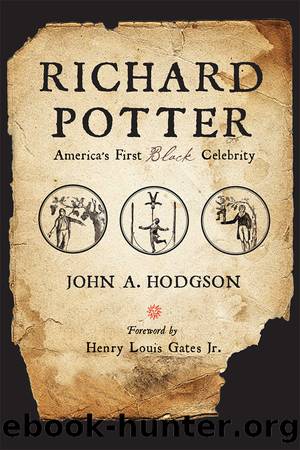

Richard Potter by John A. Hodgson

Author:John A. Hodgson [Hodgson, John A.]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: Biography

ISBN: 9780813941059

Google: Lrw-DwAAQBAJ

Barnesnoble:

Goodreads: 36868862

Publisher: University of Virginia Press

Published: 2018-02-13T00:00:00+00:00

Richard Potterâs letter reveals a man of words, not usually of lettersâan emphatically phonetic speller: âcumâ (rhymes with ârumâ) instead of âcomeâ; âCortâ (rhymes with âportâ) instead of âCourtâ; ânoâ instead of âknowâ; âthairâ (rhymes with âhairâ) instead of âthere.â It also evinces traces of the formal education that he received in his early youth or (more likely) the practical training that he received in the Dillaway business: he may misspell âwriteâ as âwright,â but then he has learned how to spell âwrightâ and has had occasion to write the word before this (Samuel Dillaway senior had begun as a housewright, and his business dealt with shipwrights and housewrights regularly). And we learn that he has a Boston accent, too: âI sor youâ (i.e., âI saw youâ) makes this very clear, and âI shall be gornâ (i.e., âI shall be goneâ) strongly indicates it as well.

He is also, beneath his courteous demeanor, a man of some spirit, as his conclusion demonstrates. He has been wronged, he feels, but he is very ready to call that injury a wrong, and he does not regard that wrong as the inevitable or acceptable lot of a black man: âif posabil punish thos villings.â

IV

The ominous financial threat of the Rhode Island suit that was hanging over Richard Potter from the moment he returned to New Hampshire in early 1824 was only one of several financial and personal burdens that now suddenly encumbered him. Perhaps, indeed, he could hope for a while that the Rhode Island case would just go away, since court term after court term passed only for the case to be deferred and deferred again (as we have seen, depositions in the case were not even taken until late April 1826). Perhaps, too, he hoped for some time (evidence suggests that he did) that other burdensâessentially, family problemsâwould, with attention and careful planning and management, go away or diminish as well. Over the course of the next two or three years, all those hopes increasingly proved untenable.

In the rural and agricultural communities of America at this time, cash could be a rare, seasonal commodity, and promissory notes were a familiar fact of life, whether they took the form of credit granted by a local storekeeper and recorded in a ledger or notes exchanged between individuals. Usually there would be no public or permanent record of these transactions; unless a mortgage were recorded in a county registry of deeds, or a contested debt ended up as the subject of a court case, or someone died intestate and the probate court appointed an executor to inventory the deceasedâs assets and liabilities, a promissory note was private business, and, once it had been honored, no record of it was likely to survive. It can be difficult, then, to assess an individualâs financial status in this period very accurately from such records as do remain today. Even so, it seems valid to say that throughout 1824 and for most of 1825 Richard Potter tended to be a lender and a purchaser, to appearances a man with both cash and confidence.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Down the Drain by Julia Fox(975)

The Light We Carry by Michelle Obama(898)

Cher by Cher(797)

Simple Passion by Annie Ernaux(747)

Love, Pamela by Pamela Anderson(602)

The Nazis Knew My Name by Magda Hellinger & Maya Lee(578)

Zen Under Fire by Marianne Elliott(562)

You're That Bitch by Bretman Rock(551)

Novelist as a Vocation by Haruki Murakami(542)

Alone Together: Sailing Solo to Hawaii and Beyond by Christian Williams(532)

The Foxfire Book of Appalachian Women by Kami Ahrens(531)

Kamala Harris by Chidanand Rajghatta(496)

Gambling Man by Lionel Barber(488)

The Barn by Wright Thompson(437)

Drinking Games by Sarah Levy(429)

A Renaissance of Our Own by Rachel E. Cargle(418)

Limitless by Mallory Weggemann(417)

Memoirs of an Indian Woman by Shudha Mazumdar Geraldine Hancock Forbes(415)

A new method to evaluate the dose-effect relationship of a TCM formula Gegen Qinlian Decoction: âFocusâ mode of integrated biomarkers by unknow(415)